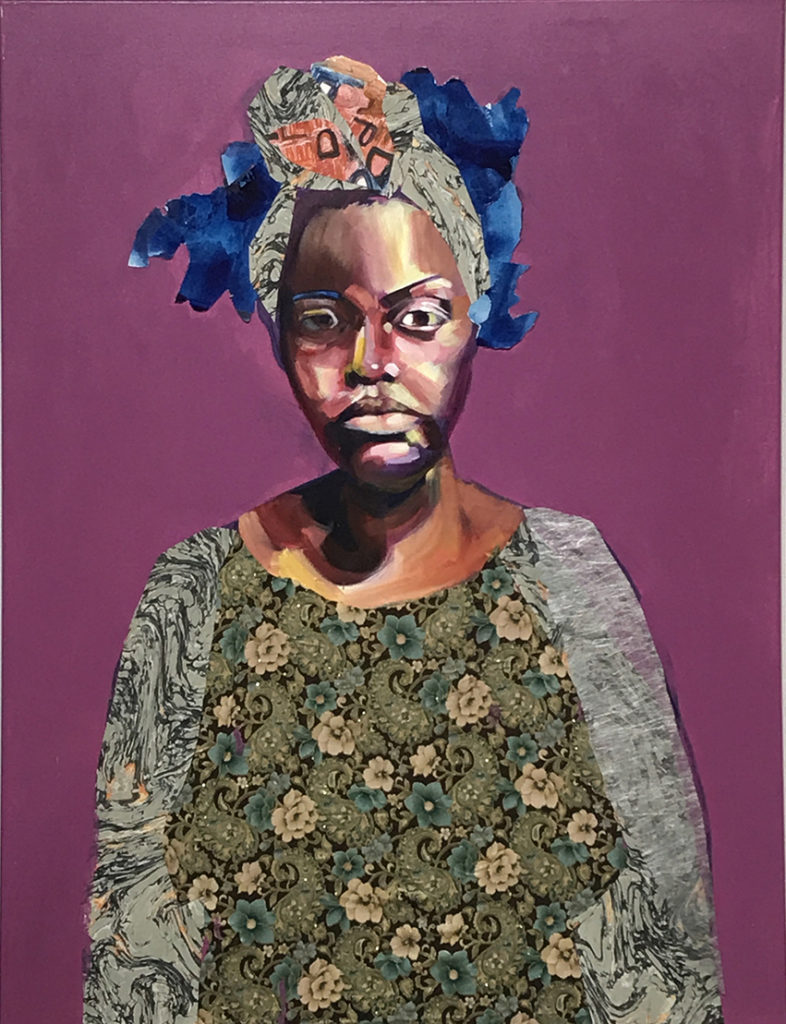

Angela Davis Johnson‘s art relies heavily on storytelling and the evolving identity of black people throughout  history. She highlights often-overlooked aspects, from their bus commutes and facial expressions during protests to their daily lives and personal style. Her textured work combines oil paints, scrap paper, and fabric — the latter an homage to her seamstress mother.

history. She highlights often-overlooked aspects, from their bus commutes and facial expressions during protests to their daily lives and personal style. Her textured work combines oil paints, scrap paper, and fabric — the latter an homage to her seamstress mother.

Johnson believes humans are geographies and landscapes of time and space and that black people, in particular, hold a beautiful magic. “We are complex and messy and simple and genius,” she says. “I’m interested in our technologies both for the purposes of survival and thriving.”

Hailing from Arkansas, Johnson has made a home for herself in the Atlanta arts community when she moved here in 2014. She’s had work displayed at Elevate Atlanta and Mason Murer Fine Art, as well as galleries across the South, from North Carolina to Texas and Mississippi. She’s currently a MINT Leap Year artist and Wonderroot’s first Artist-in-Residence.

Johnson’s current solo exhibition, BLU BLAK, is on display at MINT Gallery through July 28.

Johnson shares with CommonCreativ more about how her art helps her explore the black experience, using art as a form of activism, and why Atlanta should invest in its emerging talent.

CommonCreativ: How did you end up in Atlanta?

Angela D. Johnson: I moved to Atlanta in the summer of 2014. Prior, I had been living in Little Rock, Arkansas, working as a painter and part-time as a librarian assistant. What drew me to the city was the desire to expand and grow with my art. In my spirit, I felt I would find that here. And I did. Initially, it was really challenging being away from the arts community that I had developed in Little Rock, but once I started to become connected to artists here through organizations such as Alternate ROOTS and C4 Atlanta, opportunities, knowledge, and growth began to open up for me. I am a nomadic soul because I lived and traveled many spaces when I was a child. I still travel often, but it’s this community of visual artists, curators, performance artists, arts administrators, family, and friends that keeps me returning and rooting here in ATL.

CC: What sparked your interest in art?

CC: What sparked your interest in art?

AJ: Since I was a little one, I considered myself to be an artist. I would sing and dance and dream and draw and paint. My mother, my first teacher in many things, is a creative. She paints, sews, reupholsters, cans fruits and vegetables, cooks, bakes, writes poetry, and manifests anything. When I was 4 years old, she decided to go back to school for fashion design. What she learned in class she would share with me and my three siblings.

It was foundational for me to learn this way because the work was advanced, but I kept pushing until I could replicate anything. Later, I attended a magnet school for the arts in Norfolk, Virginia. That, too, was seminal because I was given access to equipment and skills — printmaking, oil painting, exhibition prep, etc.— at the local college and university.

When I was 14, my family was evicted from our home. We moved back to rural Arkansas and lived off the grid and on the land for several years. It is there I learned to lean into my artistry as a method of healing. I would use found objects, song, and paint to help process traumatic events, beauty, or life in general. Through my paintings, I would paint true-to-life renderings and then totally deconstruct them into odd creatures I call Think Heads. I made multiple series in this style until I redefined the my idea of visual art. I began to study artists like Romare Bearden, Carrie Mae Weems, and Wangechi Mutu.

Then I began to develop the sight to recognize the artistry of the movements of everyday black life. It was like tipping my notion of art from an Eurocentric aesthetics to something that felt more like me.

Angela Davis Johnson // Photo by Joshua Ashante

CC: Your work illustrates people of color in different settings. What attracts you to these subjects and their environment?

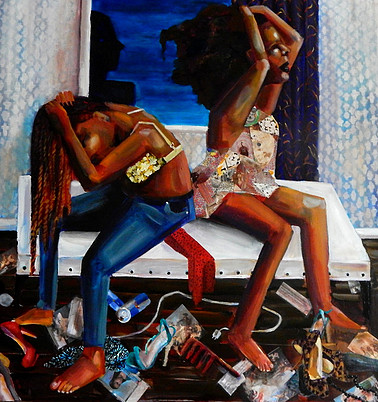

AJ: I enjoy mapping that black work visually. The subject of my works ranges from women foraging, or gathering at a bus stop to how a community processes the ancestral pain of American lynchings, or domestic violence. I created a series called “Grace Beneath the Floating World,” in which I screenshot news footage of folks protesting a police shooting of an unarmed man right after the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer George Zimmerman.

I wanted to examine who was in the crowd when so many degrading things were being said about those who were hollering out in anger. What I found and highlighted through the works was an array of humanity: mothers, young men, children, anger, frustration, and desperation. Humans. I also want to give room for dreaming in my work. It’s important for me to reflect that in whatever I am creating.

CC: There’s a liveliness to your subjects, from their facial expressions to the layers of color you use. What do you like to convey to the viewer about these subjects?

AJ: The choice of color and economy of brushstrokes I use to create the human form is my way of illuminating the soul within. Each color and mark reflects an emotion or spirit. In that coloring and layering, I [begin] to tap into something that is specific and universal. My black experience is present and also something that is past, present, and future — something that spans beyond this current moment. I get to witness through color the energy that all things possess.

It is a meditation. I think of voice and body movement in the same way as I do color and brushstrokes. Each are vibrational pathways to the soul. Finding ways of recognizing the universal within the specific is how I want to continue in my creation. That’s where the heart of my work is. I hope people feel that when looking or participating in the work.

CC: You mentioned that you use your art as activism. How do you approach that?

CC: You mentioned that you use your art as activism. How do you approach that?

AJ: Activating spaces for emotional wellness is the aspect of activism that I am interested in. We are faced with endless news of terror. There has to be a space for envisioning and creating outside of the program we are shown as our reality, in addition to the tremendous work people are doing through policy changes and disrupting societal complacency through protest. I want to continue to be a witness to their work and make space for envisioning a world worth living in.

I feel we must do something to counteract the actions and narratives of violence, fear, and scarcity, not only because it distorts and destroys who we are as a society and world, but also because our children are watching us and emulating this madness. I’ve been doing this work alongside Philadelphia artist Muthi Reed with the Hollerin Space, an ongoing interactive installation that centers spirit, blackness, and wellbeing.

CC: You often mix fabric and paint in your works. What are your favorite materials to work with? What’s on your wishlist to try?

AJ: Using materials and processes that are considered domestic or gendered is imperative to me in shaking up white-walled spaces in the art world. I often turn to fabric because it reminds me of my mother’s work. I want to try my hand at making wearable sculpture. I have made dolls turned puppets for a Will McAdams play in Massachusetts. It was amazing. I want to go deeper in that direction to watch my paintings turn into three-dimensional forms. I also want to play with light. I went to AfroPunk here in Atlanta to see Solange. The way the set was designed with those objects and light, I was completely mesmerized. I would love to play with light and body and sound.

CC: What are some of your proudest accomplishments as an artist?

CC: What are some of your proudest accomplishments as an artist?

AJ: I was told a long time ago that making a life as an artist is impossible. I am a Southern black woman who did not have a lot of money growing up. I was told I was no Picasso. That I would need a rich man to support me or an art school to validate my work. Every time I get the opportunity to share a painting, an installation, a performance, I do not take it lightly. I honor the yes.

I value the space made for me by the prayers and hopes of generations before me. I honor all the women in my family who were told no but kept dreaming anyway. Cultivating work like the Hollerin Space, where all of my artistry, voice, and presence has a place makes me so proud. Defining a space that honors all of myself is empowering and generative.

CC: How would you advise artists to promote themselves?

AJ: The greatest way of promoting your work is developing true, real, and deep connections with other artists. The tools I use such as email campaigns, Instagram, Facebook, and newsletters are only as strong the relationships I have built over time. I would suggest reaching out to artists whose work or work ethic you admire. Learn and share with them. Take art developmental courses to not only expand your knowledge but your network. Whenever I have found success, it has been because another artist has taught me something I didn’t know or vouched for me when no one knew who I was.

CC: Do you have any dream collaborations with other local artists?

AJ: For me, collaboration has been completely interwoven with my Atlanta arts experience and practice since moving here. In addition to the work I do with artists throughout the country, I have been fortunate to be surrounded by brilliant local artists from multiple disciplines such as Living Melody Collective (Danielle Deadwyler, Jessica Caldas, Haylee Anne, and Angela Bortone) and/or create a community arts engagement tool with the phenomenal artist Tiffany Lattrice, Executive Director of TILA Studios, or work alongside Charmaine Minniefeld’s Westside mural or Lauren Strumberg’s [Laura Calle mural for] Living Walls.

I love Zipporah Camille Thompson, Sheila Pree Bright, Shanequa Gay, and Jamaal Barber’s work. Working with any of them would be a plus. Elizabeth Jarrett, too! Dream collab would be Anicka Austin. Her performative work is so bright, so brilliant. I would love to dream with her and create something reflective and powerful.

CC: What do you think about Atlanta’s current arts scene?

AJ: My experience with the Atlanta art scene has been a generous one. Through the connections and opportunities, it is mind-blowing to see the talent here. However, there has to be a way to equitably fund artists directly in order to finance the cost of living here if Atlanta wants to see its talent stay and expand. That kind of support will allow artists to take more chances and experiment to create dynamic work.

BLU BLAK performance // Photo by Jessica Caldas

CC: What’s next for you?

AJ: My exhibition BLU BLAK at MINT Gallery opened in June and there will be a series of happenings until July 28. Many of the portraits will go to Bradbury Art Museum in Arkansas after the exhibition closes. I am participating in a mobile art project that I am excited about. I am also working on a large scale community art project that I am cultivating here in Atlanta. There are Hollerin Space happenings occurring in Atlanta and Philly and beyond. And continuing to expand my gifts by working in ways I haven’t before.

CC: Why do you make art?

AJ: I make art to remember who I am when the world tries to define me by my race, my gender, my socioeconomic status, my sexuality, my body, my education, my movements. I make art to remember who we are in all these messed up fragments of another person’s imagination. I make art to make myself big in freedom. Big enough to make space for my children’s children to dwell in.

You can see more of Angela’s work on her portfolio site, Facebook, and Instagram.