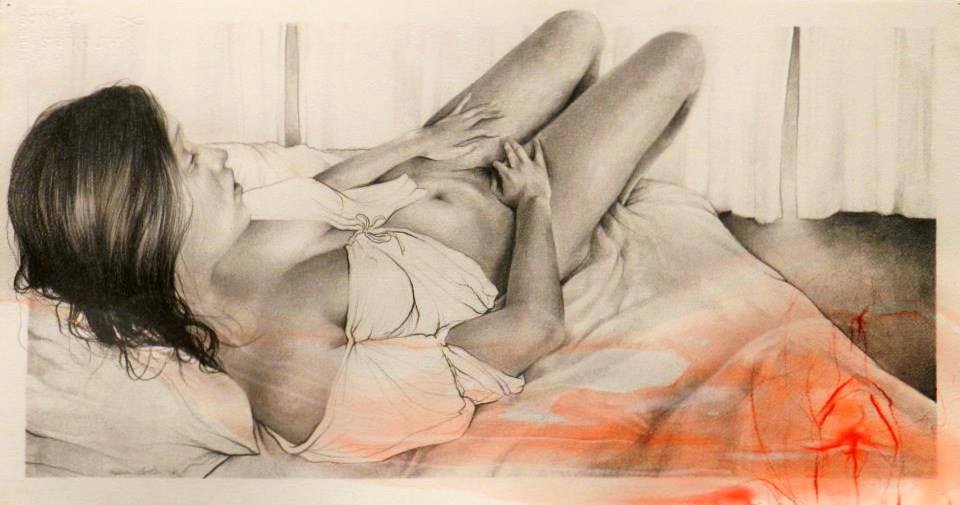

Looking at Jessica Locklar’s paintings is like peeking through the slight crack of a bedroom door, or shifting your eyes to sneak a peek at a journal unwittingly left unfastened. Her pieces feel deeply intimate, explicitly vulnerable and slightly melancholic. Beestung lipped beautiful girls draped in cotton sheets, cream-colored lace nightgowns or tangled manes of russet hair glow under candlelight — and your heart breaks a little looking into their wide glassy eyes.

Looking at Jessica Locklar’s paintings is like peeking through the slight crack of a bedroom door, or shifting your eyes to sneak a peek at a journal unwittingly left unfastened. Her pieces feel deeply intimate, explicitly vulnerable and slightly melancholic. Beestung lipped beautiful girls draped in cotton sheets, cream-colored lace nightgowns or tangled manes of russet hair glow under candlelight — and your heart breaks a little looking into their wide glassy eyes.

Jessica is not upset that you feel emotionally pulled looking at her pieces — in fact, she wants you to find them both beautiful and slightly grotesque. Jessica has explored the male gaze through female eyes, and it has left her feeling empowered. Her work doesn’t scream “sex,” it whispers it, and you may find yourself seduced and ashamed to varying degrees.

She writes in her Master of Fine Arts Thesis Paper that “because (this) work is made by a woman, they (the viewer) may feel as though their private thoughts about women are not as private and harmless as they believed.” By “watching you watch” these women in their seductive and yet contemptuous state, the vulnerability of the “female nude” is shifted to the stares of its audience and not the body before them.

Here, Jessica talks to CommonCreativ about her dark inspiration, haters, why analeptic experiences are far better than accolades, and the fearless females in her life who have allowed her to embrace the exploration of herself through her art.

CommonCreativ: How did you master your painting technique?

Jessica Locklar: Well, I’d hardly say I’ve mastered my technique, but thank you! When I was in undergraduate school at the University of North Georgia I was selected to do the presidential portrait of the retiring president of the college. I wanted it to be the very best it could be, but I didn’t know exactly how to go about it. My professor, Craig Wilson, suggested that I try and do ‘indirect painting,’ something entirely new to me. It was the biggest commission of my career but I decided, why not? What started as trepidation led to a deep love affair with the style that I continue to use.

CC: What exactly is indirect painting?

JL: For those who aren’t familiar with the technique, you start by toning your canvas — I usually use raw sienna. After that, you sketch in your composition, begin the grisaille (the neutral under painting), then you glaze on layers and layers of color. Finally you add the opaque color back in moderation. There are plenty of variations of this technique, but this has been my favorite.

CC: What’s your creative process?

JL: Sometimes I’ll see an image that sparks something in me, and I’m drawn to paint it, but with my own aesthetic. Most of the time I have a vivid vision of a completed painting that goes along with a narrative and that’s what I’m working toward.

I find a lot of inspiration in my friends — sometimes their stories, but most of the time their face. I’m drawn to the way their lips move, the curve of their cheek, even how they sit. I’m sure that I’m really annoying, yelling at them to sit still while I take their photograph when we’re just hanging out, because in that moment they are so beautiful to me and I have to immortalize them. I get my friends to model for me a lot of the time, so I have a direct frame of reference; I’ll take photos and compile them with other images in Photoshop. I’ve been doing it this way since high school, but without the technology that I have now I would make actual collages (I’m talking desperate times: paper clips, scotch tape, nail polish, even gum).

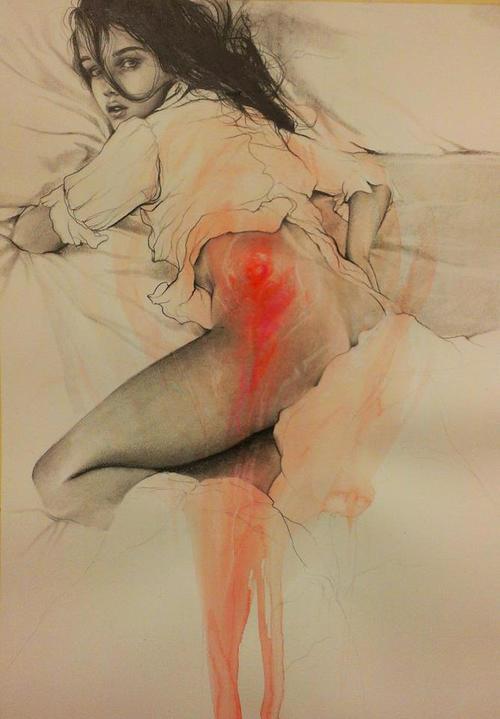

CC: You’ve said that your art toes the line between guilt and pleasure — can you elaborate?

JL: I think this is especially true of the sculptures. You see them and you think, ‘Oh my, is that… what I think it is?’ Most people become a little, if not a lot, uncomfortable. One minute they’re turned on by this illicit imagery, the next they’re feeling shameful, or uncomfortable, and confused. They’re toeing the line between guilt and pleasure as they look because they’re looking through the “male gaze.” The female nude originates in antiquity, and she has been objectified by men ever since.

My work explores the sexualized female form and the overt eroticism that is thrust upon young women once their bodies have reached their newfound, nubile form. The guilt that bubbles up from this subject matter is natural because women are brought up to be ashamed of their bodies and its daily functions. Not only is sex taboo, but just being a woman is taboo.

CC: Tell me about the backlash that your art has had. I’m referring in particular to the the man who left comments on KaiLinArt’s Instagram page saying that you were “Over sexualizing pre-pubescent girls,” and that your work was “ethically wrong.”

CC: Tell me about the backlash that your art has had. I’m referring in particular to the the man who left comments on KaiLinArt’s Instagram page saying that you were “Over sexualizing pre-pubescent girls,” and that your work was “ethically wrong.”

JL: Well, at first it stings; almost as if I myself am being rejected. My work is so deeply personal that I have a hard time separating myself from my art. This particular incident was one of the first times that I’d heard such a negative reaction. I believe it was because he didn’t know me, my story, or more of my work; he probably thought it was shock art or something. I can’t speak to why someone would feel the need to be so critical on such a public platform because I can only do so much to explain myself.

If I saw something that disturbed me as much as it seemed to disturb him then I would research the work, who made it, why they made it so I could see it from their perspective. I may not like it still, but I could understand it more on a level than just, ‘Ew, no.’ Art is a mirror you hold up to the world — maybe we don’t always like what we see.

CC: Tell me about some of the women who have impacted your life.

JL: My grandmother was a self-made woman who worked very hard. She was going to be better and stronger than anyone in her way. She was bright, diligent and beautiful.

My mother is a fierce friend, the most generous and loving soul. She is so strong and so resilient, capable of doing anything, especially if someone says no. I hold them in the highest regard.

CC: What is the greatest accomplishment of your artistic career?

JL: I think every accomplishment leads to another, so who am I to say what is the most important or significant if I, myself don’t know where past successes will lead me? I think instead of awards and milestones, I am the most grateful for the strength I had to confront my past and deal with it, sift through it, and make it work for me instead of hurting me.

CC: Who are your dream collaborators?

JL: This is tough. Can I time travel? Manet. Lautrec. Klimt. Munch. Waterhouse. Wyeth. Kiki Smith. Koons. I mean, who wouldn’t I jump at the chance to learn from the greats?

CC: What’s special about being a Southern artist? What keeps you in the South?

JL: There is a deep painful past that is still very much alive. There are so many sources of pain to make work from and it’s cathartic for me. Not that I enjoy people’s suffering and want to leech off of them and their history, but I’m ineffably inspired by triumph over pain; I relate to it. I think I’m still here in the South because I have roots here, an understanding, and generally I find Southerners to be polite, tactful, and generous.

CC: How do you feel about Atlanta’s creative scene?

CC: How do you feel about Atlanta’s creative scene?

JL: If I’m to be honest? Sometimes I feel as though people are there to ‘be seen,’ for the social aspect and the free booze! However, there are places like Kai Lin Art, ABV Gallery, and many more that I can’t even think of right now because I am terrible with recall, that are awesome and treat the work with respect, and those are so wonderful I can’t stand it. I think that Atlanta is on its way up and I’m excited to be along for the ride.

CC: What advice would you give your 18-year-old self?

JL: Finally! An easy question! Do what feels right for you, whatever it is that you are called to do. Even if people hate it, even if your parents tell you not to and ask why you don’t paint flowers, even if you second-guess yourself, make it, make it like your soul depends on it because… it does. Love yourself. Accept yourself. Know yourself and know your worth. You are strong, you are capable, and as long as you are true to yourself you can’t go wrong.

You can see more of Jessica Locklar’s work on her site and on her Instagram.