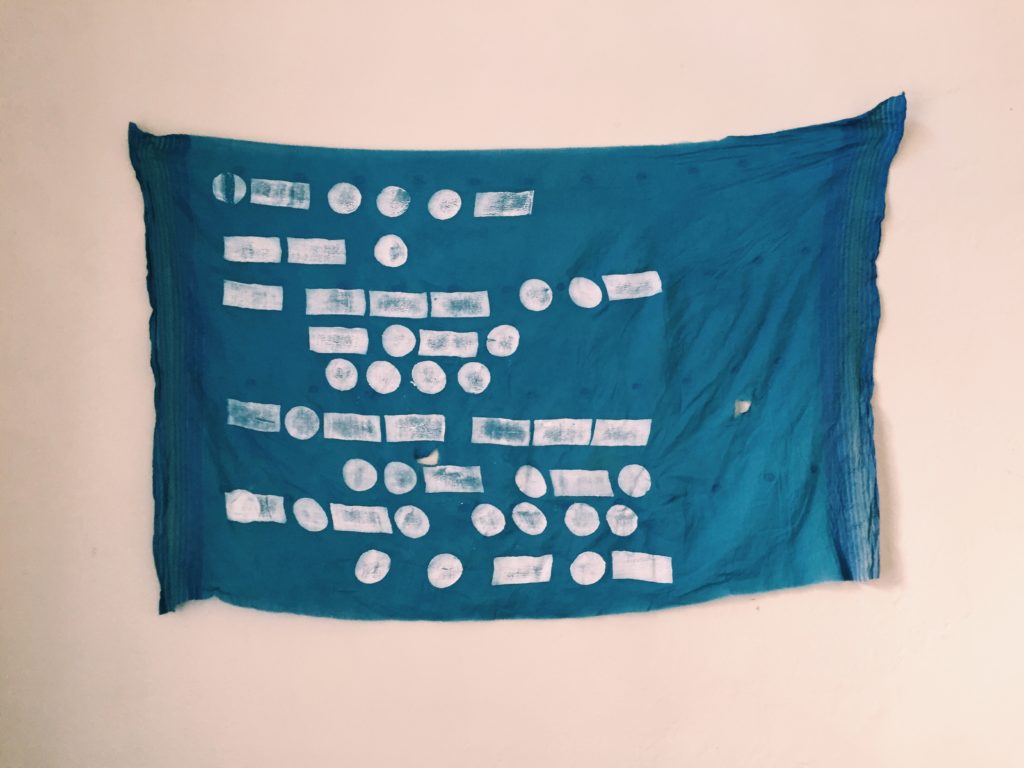

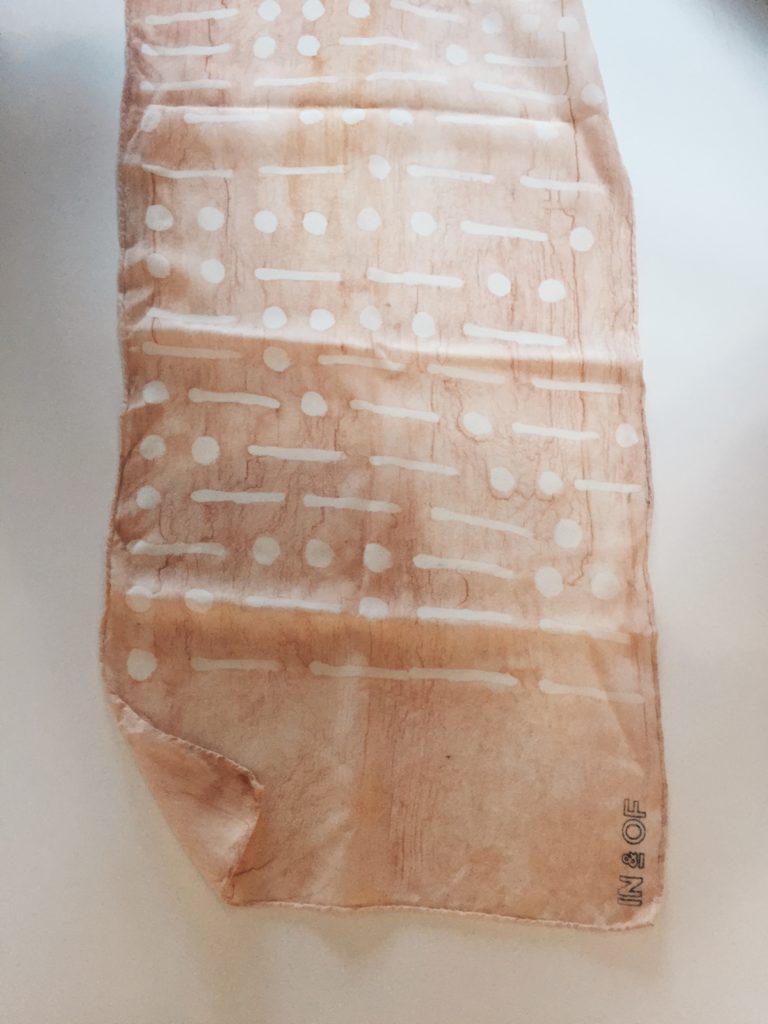

After a trip to India, Lindsey Glass found a passion for the art of textile work — she felt drawn to the infinite ideas she could express within its fibers. Her work through her business IN & OF focuses on hand-dyed textiles with secret messages in morse code, all inspired by love, loss, and grief. The simple white patterns pop against the bright hues Glass uses to dye her textiles. “It’s about the message and the color because so many of my memories of beautiful things are really just smeared visions of color — color is powerful,” says Glass. With sustainability in mind, Glass is also very careful about sourcing her materials, from silk to linen. After all, she’s an activist at heart.

Her handmade scarves and large wall flags are currently stocked at Young Blood Boutique, the Bitter Southerner’s General Store, and others spots around town.

Glass talks to CommonCreativ about her artistic process, why she uses morse code to tell her story, and her urban-planner perspective on ATL’s current arts scene.

CommonCreativ: Have you always been in Atlanta?

Lindsey Glass: I am relatively new to Atlanta, actually. I grew up on a farm in a rural part of South Georgia and lived there until it was time for me to go to college. I decided to go to Berry College, a small liberal arts school in Rome. After Rome, I lived in Athens for two years while doing Masters work in Environmental Planning and Design. There came a time I was no longer doing coursework but just researching and writing my thesis, so I moved to Atlanta. I’ve been here for going on three years. I moved here to work in urban planning — I wanted to be a community organizer. I love Atlanta, though; it’s a safe haven in a lot of senses for the South. It’s an honor to live and work here.

CC: What drew you to textile work?

LG: I’ve always been a sensory-obsessed person; I have strong reactions to sight, smell, touch, and sound. We walk around in clothing made of textile, and inspired by textile, but often think very little of it. I’ve always thought a lot about it. For a few years, I refused to buy clothing from stores, and only shopped at Goodwill. Then I transitioned to trying to only buy clothing from small and woman-owned businesses that are mindful of living wage, minimizing the environmental impact of their business, and instilling their clothing with a kind of ethic.

I became interested in textile work myself about this time last year when I was in India. Over the course of a day, I saw a man design and make the most beautiful textile I’d ever seen. There were ideas in my head, ways I wanted textiles to look, and I thought, hey, maybe I should get these ideas out.

CC: Why morse code?

LG: I started an internship with STATE, a clothing label a couple of hours east of Atlanta. [My boss there,] Adrienne, encouraged me to carve the blocks and print my designs myself. But a lot of my block ideas were rather intricate, and she told me to minimize as much as I possibly could, and to play. Then maybe a week later I was talking with someone about this impasse, and about how difficult it is to verbalize ideas sometimes, or exhausting, and I said something about wishing I could blink out morse code.

Quick blink for a dot, long blink for a dash, scrunched face for a stop, and it struck me: this is a way to involve my philosophy, thoughts, feelings, musings, all of it, in the design of a textile. Dots and dashes, they just look like pattern. Arrange them in certain ways, and bam, you have so much more. It kind of amuses me most of the time, that I make these wearable things, textiles, that are light, but something so heavy– my deepest thoughts and wishes– are inscribed on them. It’s like everyone who has ever worn one of my pieces is helping me carry the weight of my emotional baggage.

CC: Tell me about your creative process.

LG: I first started printing with two linoleum blocks I carved myself the exact day I decided on morse code as design. I was using screen printing ink, but it wasn’t giving me what I wanted. I knew I had to find a better way, and I realized that if I used batik wax as a resist, I had more room for possibility. That’s my current method — painting wax onto textile as a resist. The way I make colors is a little less romantic. I hate the colors that come straight, so I try to make them a little uglier somehow. Adrienne has always encouraged me to not be so prim about things, that something that’s a little off is infinitely more interesting that something that’s clean and easily comprehended. I’ve gotten more and more interested in color, however. At the beginning, it was all about the message.

CC: Do you work from home?

LG: I have a studio at my house. When I first started printing, I was working on my tiny porch in the Old Fourth Ward. It was insane — this porch was probably 10 feet by 5 feet, maybe smaller. I had a butcher block that I found in the dumpster I used to batik on, and I dyed everything in buckets on my porch as well. I’ve since moved to Ormewood and have more space, and I was working from my kitchen. About a month ago I made the transition from kitchen table to spare bedroom. I still dye everything in buckets in the kitchen though, and I boil out batik wax in a big pot on my stove. Working from home, especially if you’re a person whose work is to make art, takes over your life. I have serious trouble stepping away, but I like it that way. Also dye is in every crevice of everything, and so is wax, and all of my clothes, no matter how nice, are completely compromised.

CC: You hand-print and hand-dye everything. How’d you learn the trade?

LG: I thought to myself, “I am going to do this,” and then I figured out how to do it. Every method I use I stumbled into. Dyeing, printing with batik, sewing on a machine — I had no experience with any of it. I knew if I didn’t jump in and just start experimenting, I would never get very far. So I threw myself in. Now it’s all second nature, including the morse code — I’m fluent. The business side has been more guided. Adrienne at STATE has continued to ask me questions about who I want to be in this world, what I want to make, who I want to make it for, and how I want to sell it. It’s been an incredibly purifying and clarifying experience, being guided by her.

CC: Do you have a particular textile that you love working with?

CC: Do you have a particular textile that you love working with?

LG: I fell pretty hard for silk in the past couple of months. And then linen. I’m still a business baby, and I’m still working on my sourcing. Because sustainability feels like an important part of this, I’m currently working on sourcing textiles woven in the South made from Southern cotton. It’s hard, but I’m working on it. I know it will come together in the next few months, mostly because I refuse for it not to. I also know that there’s a wild world of natural dyes out there.

I am, however, interested in the color that comes from a landscape. “Weeds” growing in vacant lots, clay from ditches, many things can lend textile color. That’s something I plan on getting elbow deep in, in the new year.

Natural dyes are complicated for me because I batik. Natural dyeing requires boiling, which is directly in conflict with wax as a resist, because the resist will boil off in the dyeing process. But I am also interested in exploring alternative methods of making pattern. I have plans to use needlepoint embroidery, not to make morse code markings, but brail. So there’s that tactile element to it. One thing I am sure of: My work will always be a form of communication.

CC: What inspires you?

LG: Oh man, what doesn’t? I will always be inspired by love, loss, and grief. That’s one of the most common cycles in my life (as with most, no?) — but I’m also the type of person who, as Salinger would say, believes the world is conspiring to make them very happy. Every way I see light touch a tree beautifully, I think it’s for me. I think that’s what I’ve tapped into — a severe loneliness in my witness of the world, an awareness that we are mighty far apart, but we’re all out here, and finding the comfort and the beauty in that. My work is an attempt to communicate across those vast waters between us humans — to tell people of my experience in hopes they’ll tell me of theirs. My friend Maruti says that we are all falling, none of us has a parachute, but there is no ground — and in magic moments, we can reach out and hold hands. That inspires me because I believe it.

CC: You recently started ramping up your business — how do you promote yourself?

CC: You recently started ramping up your business — how do you promote yourself?

LG: Well, my first reaction is to say that I don’t promote myself. However, I do have Instagram, and most of my opportunities, like stocking with Bitter Southerner and Young Blood (both of which I could not be happier about) have come from buyers seeing my work there.

I try to be as genuine as possible, and honest about my life, what I’m going through, and why I made the piece I made. Patti Smith, one of my greatest inspirations and heroes, said the best piece of advice she ever got was, “keep your name clean,” and I’ve recently started to understand what she means when she says that. The only honest thing we have is who we are. The only interesting thing we can make is something that’s directly inspired by who we are.

CC: From both the perspective of an urban planner and artist, what do you think about Atlanta’s current creative scene?

LG: I try not to be political, but I’m political to my deepest core. All I can say is, condos don’t feed art, and I see an awful lot of condos being built these days. The optimist in me believes that creative people are survivors and revolutionaries, and there’s a reason oppressive governments limit artistic expression — it’s powerful. Thankfully, a lot of art coming out of Atlanta is honest and will always be more swaying and powerful than the forces that stand to squash it.

It’s all so complicated, isn’t it? That one of the biggest sources of public art in the city is in collaboration with the Atlanta BeltLine, an organization complicit in the removal of historic residents from their hard-fought communities and places of meaning. I don’t know how we sort it all out, but I would like to have more conversations about it.

CC: What’s next for you?

LG: I have several goals for the new year. Learning to weave my own textiles is at the top of the list. I hope to release a series of mini-collections on my website, and to stock in more stores across the country, if the opportunity comes to me. I hope to explore naturally occurring methods of dyeing, to reevaluate my mark-making method, and to be bolder in design. I hope to travel, and I hope to learn at least five things from five people I don’t know yet. Hopefully a slew of mentors are in my future!

CC: Why do you make art?

LG: I don’t feel I have another choice. I know that sounds so trite, but when my creative heroes say, “I do it because I must,” that resonates with me. It’s a way to keep good things alive inside me, if that makes sense. It’s my internal garden I’m tending. All of my favorite ghosts and ideas and memories live in the space that this art holds inside me.

You can see more of Lindsey’s work on her portfolio site.