Plenty of people know someone who has packed up their life in America and jetted off to teach English in a foreign country. In 2010, teaching English overseas spiked in popularity and has since become the answer for many educated but unemployed 20-somethings with a desire to travel. That same year, artist Jess Hinshaw joined the adventurous pack and moved from Atlanta to Daegu, South Korea. But instead of treating his experience abroad as “a year off” as many expats do, he decided to use his free time to focus on his art as well as liven the creative scene in South Korea. Before moving to South Korea, Hinshaw was involved at Danger Press, Atlanta Printmakers Studio and printing for Methane Studios.

Plenty of people know someone who has packed up their life in America and jetted off to teach English in a foreign country. In 2010, teaching English overseas spiked in popularity and has since become the answer for many educated but unemployed 20-somethings with a desire to travel. That same year, artist Jess Hinshaw joined the adventurous pack and moved from Atlanta to Daegu, South Korea. But instead of treating his experience abroad as “a year off” as many expats do, he decided to use his free time to focus on his art as well as liven the creative scene in South Korea. Before moving to South Korea, Hinshaw was involved at Danger Press, Atlanta Printmakers Studio and printing for Methane Studios.

Initially teaching screen printing classes out of his tiny apartment only months after arriving in Deagu, Hinshaw graduated to running his own screenprinting business, spearheading the free art magazine [b]racket, and curating art exhibitions in Daegu. He’s taught more than a dozen screenprinting classes in 2-plus years, and continues to see growth and interest in the classes. He’s taught students from South Africa, Australia, Ireland, Korea and more. But even with success in South Korea, he finds that there’s always something to miss about Atlanta.

CommonCreativ: What prompted your move from Atlanta to South Korea?

Jess Hinshaw: I was just working too much. I was teaching art at two different universities, working full-time but getting paid part-time wages, with no benefits or health insurance. To fill in the gaps in money I was doing catering gigs at night, and working as a bartender a few nights a week. I was also working on art when I could, visiting my studio to get work completed for potential shows. My wife and I wanted to travel, and it seemed like a good time since neither of us had a permanent-type job. We knew we couldn’t just go somewhere for a few months without income, so we took jobs abroad with the idea that it would facilitate traveling and allow us to save as well.

CC: Did you feel like it was more difficult or easier for you to make art in a foreign environment?

JH: One thing I tried to build in Atlanta was a community with artists. Most of my friends were in a similar situation: We were all teaching art, making art, living and breathing art. I started a group called Art Beers. Our goal was to drink beer and not talk about art, but stay in touch for the networking potential and to have a sympathetic ear to listen to eachother’s bitching. We met weekly for about a year and it was a lot of fun. When I got to Korea, once the culture shock calmed down, I began looking to build a similar group. I started teaching screenprinting classes in my apartment in hopes of finding other artists. I basically did the same thing in Daegu as I did in Atlanta: I found about six people who were serious about art. This time though, the goal changed. There wasn’t enough art around, so this group focused on producing work, publishing zines and having group shows. We met in the morning once a week at a coffee shop, so the name changed to Art Beans.

Making art here [in Daegu] has been challenging and relaxed in different ways. It is difficult to define your audience here because the East and the West are so different. Cultural keystones we take for granted aren’t part of the vocabulary here and vice versa. For instance, you couldn’t do a piece of Glenn Beck fans drinking kool-aid because no one knows who Glenn Beck or Jim Jones are. That being said, people here are very eager to see what foreigners are doing, and because of that a lot of doors have opened much easier than they would have back in Atlanta.

Making art here [in Daegu] has been challenging and relaxed in different ways. It is difficult to define your audience here because the East and the West are so different. Cultural keystones we take for granted aren’t part of the vocabulary here and vice versa. For instance, you couldn’t do a piece of Glenn Beck fans drinking kool-aid because no one knows who Glenn Beck or Jim Jones are. That being said, people here are very eager to see what foreigners are doing, and because of that a lot of doors have opened much easier than they would have back in Atlanta.

CC: What’s your take on the current art scene in South Korea?

JH: From what I see the scene here is sort of stuck in the middle of modern and classical ideas of art. There is a strong emphasis on technique, which can be refreshing, but really how many photorealistic paintings do you need to see? Conceptual art is still not a common thing to see in a gallery in my experience. That being said, artists like Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami are adored here. Maybe that has to do with the “cute” factor, which Koreans are huge fans of. It’s strange, world-renowned artists show their work here and people flock in the millions to see it, but it seems the art itself is of secondary importance. When I’ve gone to major exhibitions here, most people are taking their picture next to the painting instead of looking at it. Then they go to the museum cafe and look at the picture they just took of themselves next to the painting.

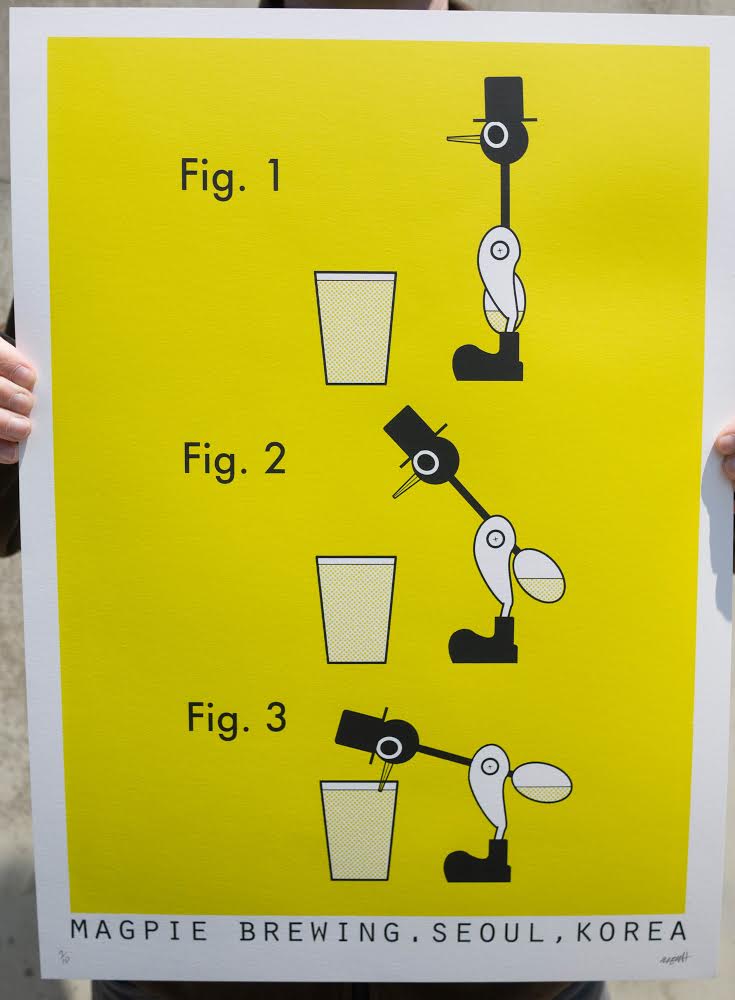

I should also note that I have been living in the most conservative major city in the country for four years. I think Seoul has a much firmer grasp on what it is to be an artist in the 21st century, and there are plenty of artists that are doing noteworthy art here. I’ve been lucky enough to become friends with Jung Yeondoo, one of the most important contemporary artists in the world. His work is constantly evolving and performing on as high a level as any other big name in art.

I should also note that I have been living in the most conservative major city in the country for four years. I think Seoul has a much firmer grasp on what it is to be an artist in the 21st century, and there are plenty of artists that are doing noteworthy art here. I’ve been lucky enough to become friends with Jung Yeondoo, one of the most important contemporary artists in the world. His work is constantly evolving and performing on as high a level as any other big name in art.

CC: How did [b]racket magazine come about?

JH: One thing all foreigners here are given is a lot of free time. That paired with the fact that you don’t have pre-existing relationships here to nurture leaves most people thinking about ways to fill their time. Some do that by watching every TV show ever, but I wanted to do something art-centric. I traveled to a nearby city, Gwangju, within a few weeks of being here and found that an expat was publishing an art magazine there. I was jealous; I wanted that for Daegu. Two years later, I had found two friends that I thought could help that magazine become a reality. While drinking beers on a rooftop one night, we decided to start publishing [b]racket.

CC: What was the response to the magazine like?

CC: What was the response to the magazine like?

JH: That has been hard to measure. Friends have been very kind with their compliments, but it’s been difficult to get a non-biased opinion. We published for two years, and I’d start to hear things like “Oh, you’re the [b]racket guy!” so at least people knew it existed. We were able to get funding by the city government for printing for a year, so that could mean some people believed in it. I think artists were very appreciative of it. We did it so that young artists could have a way to share their work with others, and build community here with artists. I think we did as good a job as we could with that.

CC: What art have you been working on recently?

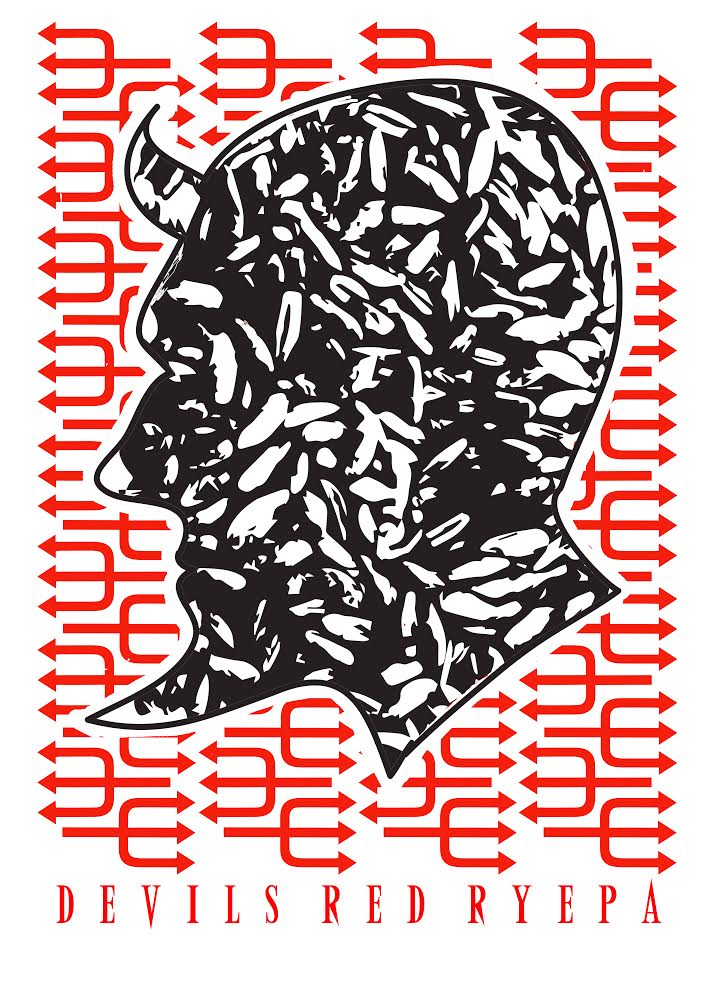

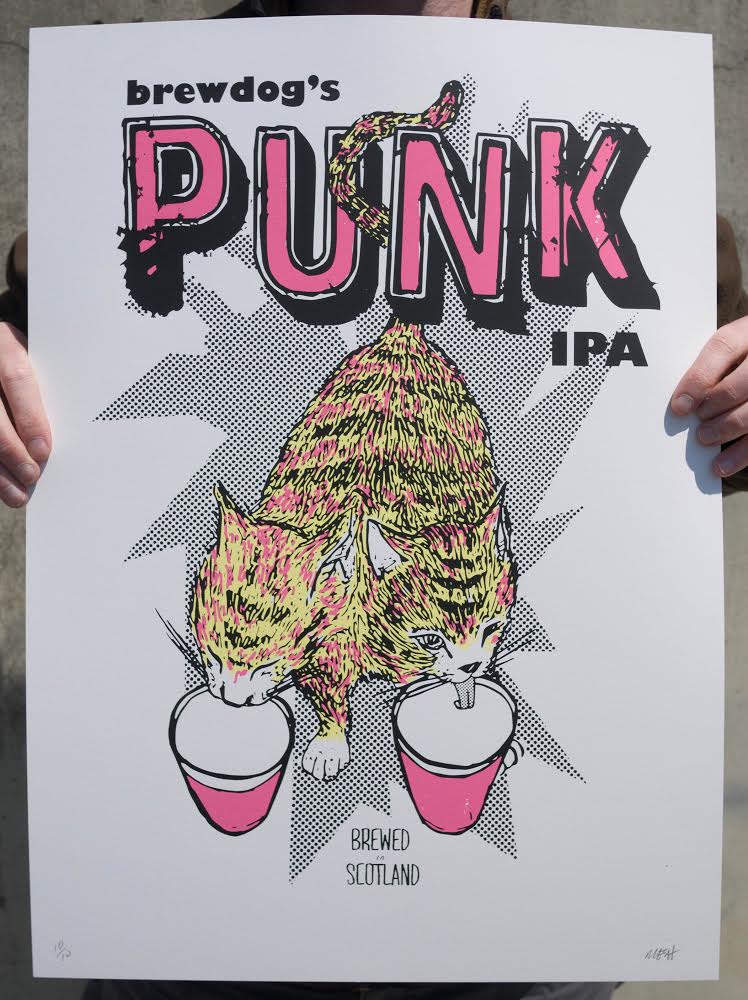

JH: I started a screenprinting company called MESH with my friend Chris, who was also the designer for [b]racket. We recently decided to stop publishing to focus more on screenprinting. I’ve been spending most of my time printing and designing for clients and a few publications around here, as well as some logo designs and shirt printing jobs.

CC: Art related or not, what do you miss the most about Atlanta?

JH: The familiarity, I guess. Even having been in Korea for over four years, each day is an adventure. There is something to be said for the mundane, although you don’t appreciate it until you don’t have it. I miss the dive bars, and places like the old Lenny’s and the Yacht Club on Euclid. The drinking culture here is alive and well, but it centers around eating and getting blackout drunk every time. I miss getting on a bar stool for a relaxing beer or two.

You can view Hinshaw’s screen prints here and past issues of [b]racket are available for viewing and download here.