In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, a group of citizens is chained to a wall, and can only perceive and understand the shadows projected on the opposite wall in front of them. All they know is this—a small, shadowy representation of reality.

In this vein, artist Nathan Sharratt embodies some of the most useful and powerful qualities of a transformative contemporary artist, the traditional breaker of those chains of perception. His work tackles questions of inner and displayed identity and its maintenance, the gaps between biological reality and societal expectation, the role of the artist-critic and the citizen in a digital, censored, and cross-media world, and most of the other questions your mom warned you to leave under the rug.

His toolkit is as ambitious as it is varied: Sharratt uses 3-D printers and scanners, body parts, edibles, niche typography, found objects, code errors and viewers’ expectations. His concepts are personal, yet engaging and accessible. Even performance and bare process are not off-limits, and seem as vital to our digestion of the work as any material on or near the gallery wall.

CommonCreativ talked to Sharratt following the conclusion of the mixed-media multi-artist show In Translation at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center and the beginning of his Indiegogo campaign, These Colors Don’t Run. We discussed his methods, and how to stay on your toes in an art scene in flux.

CommonCreativ: Your inspiration seems to come from an eclectic mix of sources. Is there a pattern to your source material or does it vary with each project?

Nathan Sharratt: Both. There’s definitely a pattern; it also varies to a degree with each project in terms of execution and aesthetic. But the root source of all my work is the same: who am I and how do I fit in the world? The universe is amazing and incomprehensible. Being a person in the universe is amazing and incomprehensible. The universe is too big and my mind is too small. How can you possibly reconcile how tiny we actually are compared to everything else and still find meaning in life?

Ostensibly, we shouldn’t be able to. Since we interact with the universe through a body, we tend to scale the universe in relation to how big or small it is compared to our physical presence. We’ve used technology to create culture and progress socially much faster than our brains could adapt evolutionarily. Our culture has leapfrogged our biology, thanks to technology. This is neither good, nor bad, nor neutral. We’ve created systems and structures through social culture to fill the evolutionary gaps, but they’re incomplete and imperfect. I’m interested in those imperfections.

As an artist and a person in the world, I dwell in that space in-between; where connections aren’t linear, and we’re not so boxed in by predetermined categories that we or someone else installed. When we let go of those constraints we’re much more able to find true connections.

CC: How does the manipulation of materials and texture affect your process?

NS: I love finding new materials to play with. It allows me to forget all the rules I’ve beat into my head and brings me back to a state of childlike wonder and awe as I learn a new process or material. It’s seductive, and that’s always the danger. Like Sol LeWitt said, new materials do not constitute new ideas, but they do allow my ideas to find new mutations and experiences. The material is the body of an idea, and that physical manipulation—especially when I’m working with mechanical- or computer-based production methods—gives me a sense of immediacy that I find very important.

CC: What software do you use for 3-D renderings?

NS: I use all sorts of software. Whatever gets the job done. For 3-D scanning I use Skanect with an XBox Kinect sensor. For modeling I primarily use Rhino, because it’s good with real-world dimensions and 3-D printing. Maya’s great for animation, but measurements are all relative, which makes it more difficult to plan physical sizes for 3-D printing. I also use Meshmixer, 123D Catch, and whatever else I can find on the internet to produce the desired result. For plotter drawings I use Adobe Illustrator with some 3rd-party plugins for halftones and send them to a CNC plotter.

I think there’s a misconception that if you use digital tools to make art you’re somehow cheating and the machine’s doing all the work, so therefore the work’s not as valuable or something. I wish there was a “make art” button, but there’s not. As an artist you have to know your tools, whether it’s paint, camera, wood, computer, whatever. Each has its own language, and each requires an artist to make decisions.

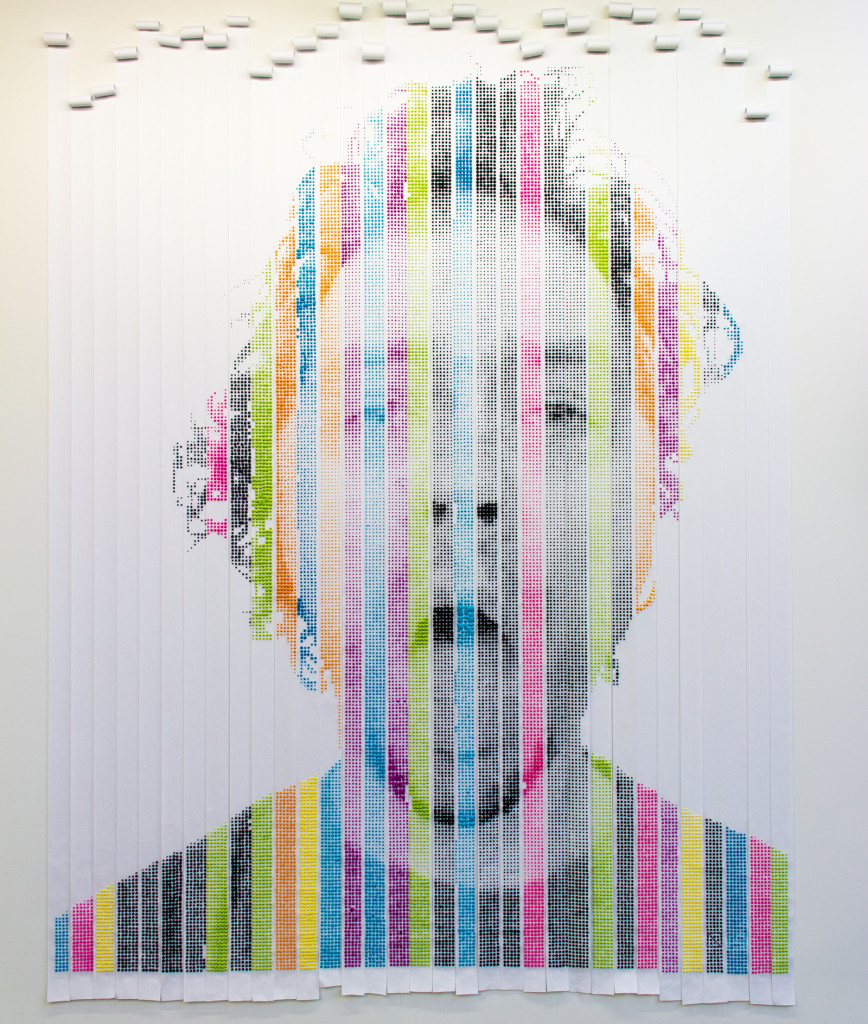

CC: Your piece “Bathroom Selfie in Sugar and Spice and Also Ants” is striking, evoking early laser printers and digital pointillism on a huge scale. Do you think that piece is a faithful representation of yourself as an artist?

NS: I suppose we’d have to define what “faithful” means, but I think it’s representative of me as an artist in how it functions in combination with ligatures. They’re a binary system that represents inward and outward modes of self, and how that self interfaces with the world. They both use self-portraiture to engage the world, and they both consider how we find meaning by connecting small pieces of information together to form a greater extrapolated whole, but they function very differently in terms of both construction and reception.

Where [the] Ligatures [exhibit] worked from inside to outside, Sugar and Spice works from the outside in. The presentation allows for an immediate experience that changes based on your relative position. From far away, the bright colored dots optically blend to form an image of a face with its mouth open. Up close, the face disappears and there’s nothing but dots and color. You’re then able to consider the parts individually, including the material and what that might mean.

For me, it’s about memory and labor. I remember eating those candy dots on strips of paper as a child and having to spit out the paper remnants that got stuck in your teeth. There was a pronounced element of labor involved. You got the sweet thing you desired, but the process had unwanted artifacts that needed to be removed; a cycle of ingestion and expulsion. The visceral act of biting off the candy, with the ordered structure of the neatly arranged rows and columns of dots created a synergistic relationship that was synecdoche with my creative process.

CC: How do you think digital media has affected the way we experience art, and will affect it in the future?

NS: I think we see a lot more of it on screens rather than in person. It opens our experience with art in terms of accessibility, but closes it in terms of intimacy. We have trained ourselves to consume in smaller and smaller bites of content. We don’t read article—we read listicles. We don’t invest in a deep understanding of a few topics—we get a surface read of many topics. We don’t look at paint—we see jpegs. Conversely, we’re becoming more and more comfortable with sending very private images or information about ourselves into the public and perpetual arena of the internet. This is all a byproduct of the ease of information dissemination and consumption that digital media allows. Our culture production is outpacing our ability to meaningfully process it. But unless some sort of zombie apocalypse happens, it’s not going away, so we’ll eventually figure out how to manage a balance between the digital and the analog. Or we won’t.

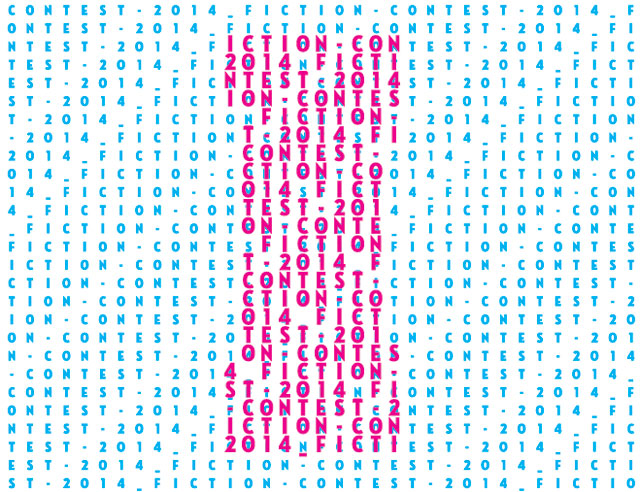

CC: You did the cover art for the 2014 Creative Loafing Fiction Issue. How do you feel about working in two dimensions? Could you see yourself doing more design work in the future?

NS: I work constantly in two dimensions. There are tons of drawings all over my studio, they just tend not to be shown as much in Atlanta in relation to my installation or performance work. I always make drawings to show with my installations, but by the time of the exhibitions, they don’t seem necessary, so they usually stay in the studio. I also spent a decade working in commercial art and magazine design in New York City before moving to Atlanta in 2008, so the Creative Loafing cover was kind of a return to form for me, except this time I could push the limits of the format. In fact, in my first draft, I pushed a little too far and broke the format. But I’m very happy with what went to print and I’m grateful to CL for giving me the opportunity to challenge expectations. So yes, I can see myself doing more design work in the future.

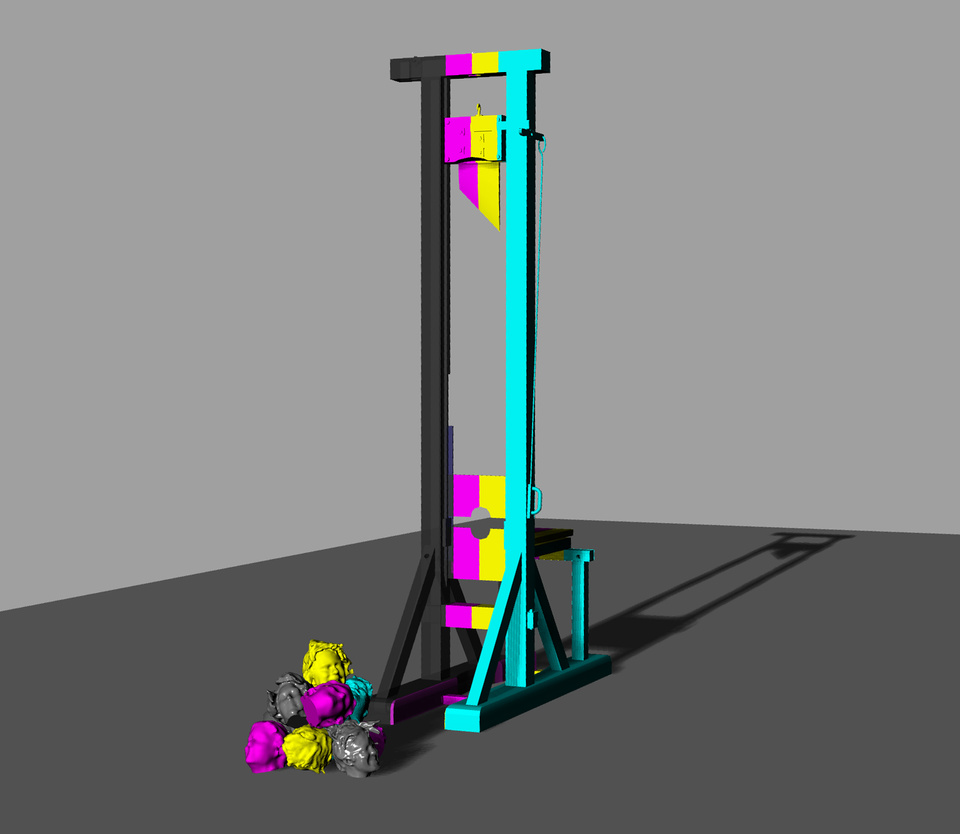

As a fun little trivia bit, my proclivity for the color palette of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black comes from my days in magazine design and its CMYK printing process.

CC: What do you think of Atlanta’s current creative scene?

CC: What do you think of Atlanta’s current creative scene?

NS: I think it’s growing in a positive way. It has its problems, like any creative scene. Institutional censorship is apparently rampant: The High Museum of Art won’t allow any male nudes; MOCAGA recently asked an artist to alter his work to be less offensive; and he chose to remove the work instead; SCAD censored a male nude during an open studio night when I was an undergrad’ and then of course Daniel Papp’s recent censoring of Ruth Stanford’s installation. And those are just the cases I stumbled upon or experienced firsthand—I can’t imagine how many are occurring that you don’t hear about. Artists and curators need to stand up and claim their right to free speech, and not be afraid to rock the boat, even if they do end up falling out. Someone will always be there to pull you out of the water.

On a positive note, the community is very strong. People are open and willing to make things happen. I wouldn’t be a fine artist if I hadn’t moved here and had the support of so many wonderful people I’ve met. The next step is getting collectors excited about collecting Atlanta artists so we don’t keep bleeding talent to other cities.

I recently experienced Zzz zzz zzz zzz zzz by Queersar at MINT Gallery. It was exceptional. So many people are doing really interesting things it’s hard to keep track these days. Sarah Shipman is doing a participatory project on burdens. AnnaLee Burnstein is working on a sculptural fashion exhibition to benefit Alzheimer’s research. Maggie Ginenstra and Mike Stasny have been doing a month-long residency at MINT Gallery called Sumptuary, where they’re curating a ton of awesome artists and events (myself included). Stephanie Dowda has beautiful black and white photographs at Get This! Gallery that I snuck a peek at in her studio.

NS: On April 19th I’m doing a performance and DJ set/sound installation at MINT gallery for Maggie Ginestra’s and Mike Stasny’s Sumptuary with High Museum contemporary curator Michael Rooks. It’s about problems that arise when we rely too heavily on binary systems (gay/straight, male/female, haves/have nots, 1s/0s). It’s called Broken Dance Party For Sexy Binaries and consists of popular dance and pop songs that I’ve broken apart and manipulated both subtly and overtly (for example, the famous and amazing bassline from Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean replaced with a single repeated note while the rest of the song remains the same). While Michael and I are performing, White Gold will be doing some tape manipulations and karaoke and I don’t even know what else, but it sounds awesome.

The performance involves Michael and me working as gay or straight bouncers. You announce yourself as either one, get a conspicuous stamp identifying yourself as such, and then you can go in and enjoy all the awesome stuff inside. If the bouncer for your particular orientation isn’t present or is on break, you can wait, leave, or switch teams. We’re very strict about the rules. However, like any oligarchy, we’re also easily corruptible and will participate in bribes, back-room deals, and cronyism for those who are determined that the rules don’t apply to them. Those people who succeed in gaming the system will be rewarded with special perks during the night, like artwork, special experiences, or access to the VIP area. You could even get appointed as a bouncer yourself. (That’s a hint for those paying attention who want to get a head start)

After Sumptuary, I’ve got the Walthall Fellowship exhibition at Zuckerman Museum of Art on May 17th. I’m working through issues created by technology interacting with the body and the problemitization of power fantasies built around powerful objects, like the 1792 guillotine and the 3-D-printed gun. All in a glowing consumerist CMYK color palette.

CC: If you had a 3-D printer without any size constraints, what would be the first thing you’d create?

NS: The world at 1:1 scale.

See more of Nathan Sharratt’s work in his portfolio and support his new Indiegogo campaign, These Colors Don’t Run, here.