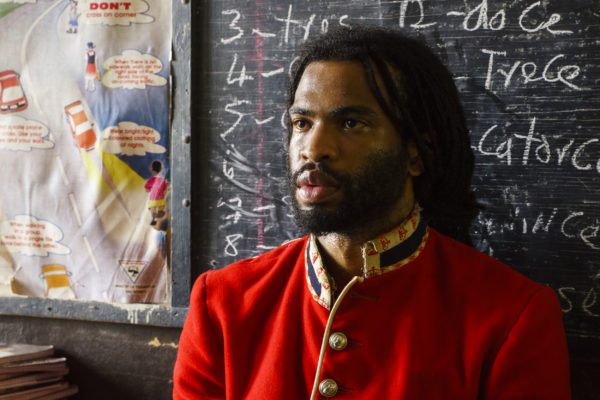

There’s a kid in all of us, sure—but Michael Klapthor‘s may get a little more time in the spotlight. You may have seen him around town at shows like the Indie Craft Experience, Borderline gallery and the Mini Maker Faire. Going on a decade of working with ceramics, Klapthor uses clay and metal to create sculptures of robots, droids and automatons with personalities of their own. His machines, inspired by video games like Megaman and Astro Boy, are crafted lovingly and skillfully, with a playfully menacing and worn-in aesthetic. They invoke a mechanized future, where Arena Fighting Robots and Physical Therapy Assistant Robots grin back at you from behind soiled and rusty mouth-grills. Despite this fact, Klapthor is realistic about the continued mechanization of modern society and, for now, his machines only power-up in our imaginations.

There’s a kid in all of us, sure—but Michael Klapthor‘s may get a little more time in the spotlight. You may have seen him around town at shows like the Indie Craft Experience, Borderline gallery and the Mini Maker Faire. Going on a decade of working with ceramics, Klapthor uses clay and metal to create sculptures of robots, droids and automatons with personalities of their own. His machines, inspired by video games like Megaman and Astro Boy, are crafted lovingly and skillfully, with a playfully menacing and worn-in aesthetic. They invoke a mechanized future, where Arena Fighting Robots and Physical Therapy Assistant Robots grin back at you from behind soiled and rusty mouth-grills. Despite this fact, Klapthor is realistic about the continued mechanization of modern society and, for now, his machines only power-up in our imaginations.

CommonCreativ talked with Klapthor about his inspiration, his creative process, and how to avoid the looming robot apocalypse.

CommonCreativ: How did you get your start?

Michael Klapthor:I studied studio art in college, so I had a healthy sampling of many different mediums. Clay, for me, gave me a tactile experience that no other medium did. I had the most direct contact and the truest results. Practicing other mediums, particularly 2-D, always felt a little lacking, like I did a facsimile of bringing the subject to life, but not really. When I made a clay sculpture, I really felt like I’d given my idea life. It had heft; I could walk around it; my thought now had a physical presence in the world. That’s probably why I pursued figurative sculpture. Some kind of minor God complex.

CC: What first inspired you to create robots?

MK: I started thinking about using the pottery wheel as a sculptural tool a while back when I taught a clay summer camp to some little kids. They were having fun, but the truth is that learning to make pots on a wheel is challenging, and these kids were just having fun making a mess. That was fine, except their paying parents want to see some results, so I had to do a little quick thinking. We turned their weird lumpy pots in an oceanscape with coral and tube sculptures, which everyone liked much better than trying to use them as actual vessels. That got me to look at the wheel a little differently, as just another tool to achieve a certain look. Later in my career, I was asked to participate in a sci-fi themed art show, and this idea came back to me. The lighthearted theme of the show gave me some freedom to experiment, and I was really happy with both the process and the outcome. It became my first sold-out show, so I figured I was on to something.

|

|

CC: Describe your process.

MK: The larger pieces begin with lots of robot doodles. These pages end up looking a lot like a fifth grade boy’s notebook with all the laser blasting eyes and explosions—not integral to the design but hard to resist. Once I’ve doodled enough to get a design I really like, I need to break it down into the various pieces I’ll need. I sit at a wheel and throw about 30 or 40 seemingly mismatched little cups and bowls until I’ve got all my parts. They take a day or two to dry a bit, then I’ll begin assembling them together. This is my favorite part of the whole process, and I get that same meticulous satisfaction I did as a kid when I would build a new LEGO set. Some of the pieces have to be cut up or altered in some way, but I only use the parts I throw on the wheel, no handmade additions. It’s a rule I made up for myself to add a challenging element in the design, and it keeps the robot looking sleek and machine-made.

CC: How do the materials you work with influence the look and spirit of the pieces?

MK: Forming these shapes with a potter’s wheel, then layering them with metallic stains and glazes gives the exact look of a manufactured, metal robot with sleek, geometric lines and genuine rusty bolts and hinges. Truthfully though, they’re really all unique and handcrafted in a very traditional art form. I like this secret about these pieces, and that a viewer might have to look a little closer or learn a little more before this becomes apparent.

CC: Your pieces have a grounded, broken-in aesthetic. More WALL-E than EVE, if you will. What drew you to that?

MK: I think the worn out and tired look implies a rich context and helps to give the character a personality. A shiny new machine has limitless possibility, it’s like a blank canvas. One with some wear and tear comes from a place of hard labor, which I find endearing. I tend to sympathize more with the downtrodden underdog character in most stories.

|

|

CC: How do you see the dynamic between people and machines changing?

MK: Despite this fascination with robots, I’m ironically a bit of a technophobe. I only recently (and reluctantly) started using a smartphone, and I’m still wary of them. I think people should have a healthy respect for technology and how big of a roll it plays in our lives. New innovations that come along aren’t always neccesarily beneficial—they just change the world around us, and sometimes in exclusionary or invasive ways. I’d love to see a cooling of techno-love, though if I had to say what I thought we’ll look like in thirty years, I have a bad feeling those goofy Google glasses will finally be acceptable and everyone will wear something like that.

CC: How do you feel about Atlanta’s creative scene right now?

MK: Atlanta has been a great scene for me so far. I feel like it’s got so much art potential and energy, that we’ll soon really see some major artists coming from this city. Right now though, there isn’t that pretention you might find in a bigger city, so there’s so much room for great ideas and experimentation. I’m truly glad to be in this town at this time.

CC: Who are some of your favorite artists or projects in Atlanta?

WonderRoot Art Center is where I run the ceramics studio, and it’s been a huge stepping stone for me and my career. I’ve been involved in a number of their projects and shows that embody that vibe of energy and experimentation, as well as met some great artists that are bringing a lot of innovative ideas to the table. I’ve also been involved the Atlanta Mini Maker Faire for the past few years, and I’m really excited for this to be in our town. We had enough attendees last year, in fact, that I believe we can ditch the “Mini” and officially join the ranks of these huge events that are happening all over the country. It’s like a huge science fair for both grown-ups and kids, an exhibition of artists and inventors displaying their weirdest and most impressive innovations. I had a hard time staying put at my booth, there were some many incredible things going on I wanted to run off and go check out.

MK: I really love working on this series, but I have a difficult time figuring out where to take them. On one hand, they would make brilliant toy designs, and I wonder if I’m limiting myself by keeping them as one-of-a-kind clay sculptures. I’m intrigued by the idea of pop art and the vinyl art toys and such, and I like how that movement has embraced a whole new type of artist that was, until recently, shunned by the legitimate art world. Taking that idea further would probably result in some sprawling futuristic porcelain factories that I would love to see realized in a gallery setting. So, probably like every working artist would agree, I need about 10 days in my week to finish every project I’m thinking of.

CC: Finally, what are your favorite machines?

MK: And I am STILL waiting on the hoverboard, which is long overdue. When I first saw Back to the Future Part II, nerd that I am, I drew a plan to make one that involved repelling magnetic forces. I recently learned that’s essentially what powers those high-speed trains that so many other countries have. It’s probably time we showed them up and put that idea on a skateboard, right?

You can see more of Michael Klapthor’s work here.