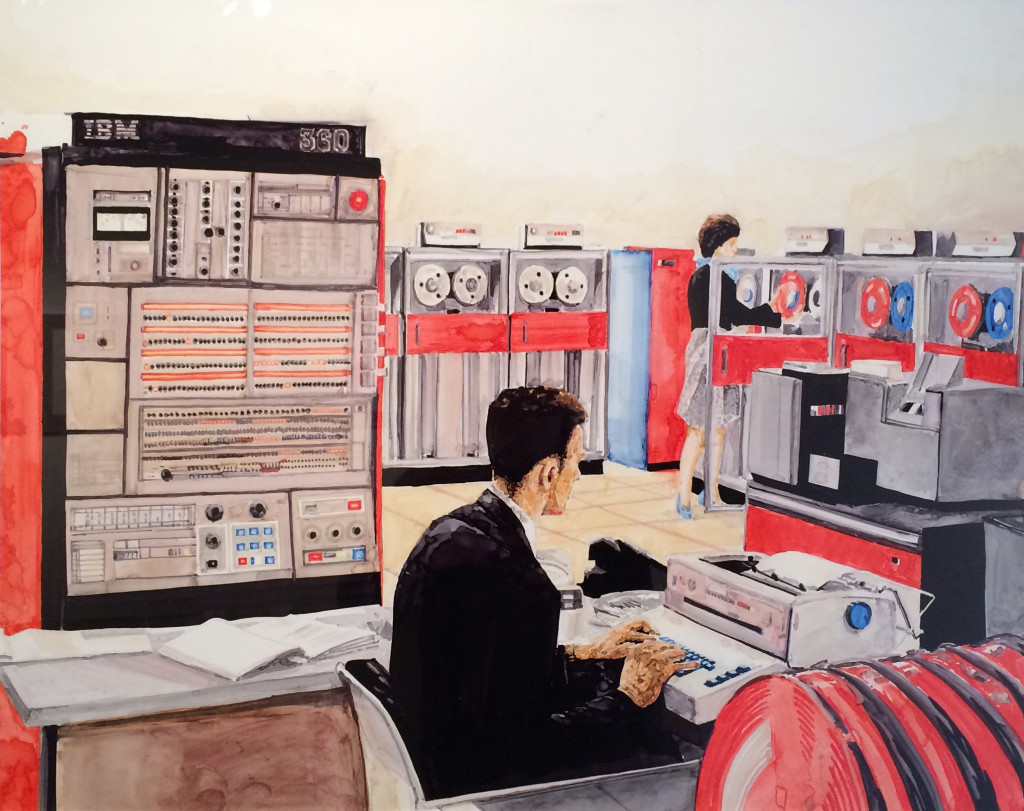

The hauntingly dystopic images found in many of Jason Kofke‘s drawings and paintings portray a cautionary presentiment and diffidence toward modern society. His works prominently feature the disconcerting interface between humans and an increasingly technological world. Referencing iconic cultural mile-markers such as NASA, personal computers and the automobile, Kofke’s art shows both a profound attraction to and admonition of modern society. Through his exploration of the seemingly grim pitfalls of contemporary life, Kofke maintains a tenaciously optimistic mindset that humanity is destined for a greater good. It’s precisely this juxtaposition of ideas, along with stark lines, vivid textures and unexpected media, that make his work so mesmerizing.

The hauntingly dystopic images found in many of Jason Kofke‘s drawings and paintings portray a cautionary presentiment and diffidence toward modern society. His works prominently feature the disconcerting interface between humans and an increasingly technological world. Referencing iconic cultural mile-markers such as NASA, personal computers and the automobile, Kofke’s art shows both a profound attraction to and admonition of modern society. Through his exploration of the seemingly grim pitfalls of contemporary life, Kofke maintains a tenaciously optimistic mindset that humanity is destined for a greater good. It’s precisely this juxtaposition of ideas, along with stark lines, vivid textures and unexpected media, that make his work so mesmerizing.

Born in the befittingly named town of Media, Pennsylvania, Kofke spent most of his childhood in small town south Florida. Acting as a stopping point for many northern snowbirds, the area had a nearly constant stream of visiting artists and patrons. Heavily involved in theater productions from a young age, Kofke’s early life was steeped in various artistic influences both contemporary and classical. Jason Kofke currently resides in Atlanta, where he continues to work with traditional media as well as participate in distinctly new fields, including mural work, through his residency with Living Walls.

CommonCreativ: What can you tell us about your background as an artist?

Jason Kofke: The day the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded overhead is the day I became an artist—I was seven years old in 1986 and living about an hour from Kennedy Space Center in Vero Beach. I recall seeing the event while in the playground of my primary school, and I mostly noted people’s reactions to the event more than the event itself. I could perceive the emotions and reactions of the adults around me and could comprehend the gravity of the loss, but this introduction to catastrophe—to the unexpected—instilled in me a multitude of questions about people and the future. Those questions are fundamentally still the ones I explore in my work. Further, I was dyslexic, and at that age learned to express my ideas and work out my problems via images rather than words. Words were, and are sometimes still, just codified squiggles with no meaning [to me].

Throughout primary schooling, other students viewed me as an artist. It was no surprise I ended up at SCAD. It took a few years for me to pull off the funding and loans, but I eventually got in. After the BFA in painting, I continued on with an MFA in painting and printmaking at the Atlanta campus, and that’s how I ended up here in ATL.

CC: How did you transition from your studies in fine art to your current projects?

JK: In college, I was a prolific painter. I never went out much, and spent most of my time in my studio or reading. When I stumbled upon Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media, his ideas crushed my concept of art. McLuhan points out the importance of a medium to any message that it conveys; that the medium is [more important than] the message. As a student of painting, how was I to digest this theory I came to believe? If the fact that I was making a painting was more important than what I was painting, why should I care at all about what I paint? Since my questions typically revolve around how humans are to comprehend the uncertainty of the future, I began offering optimistic encouragement regardless of the situation or conversation I found myself in. I guess this could be called performance art, but I’ll let the art historians delineate the divisions.

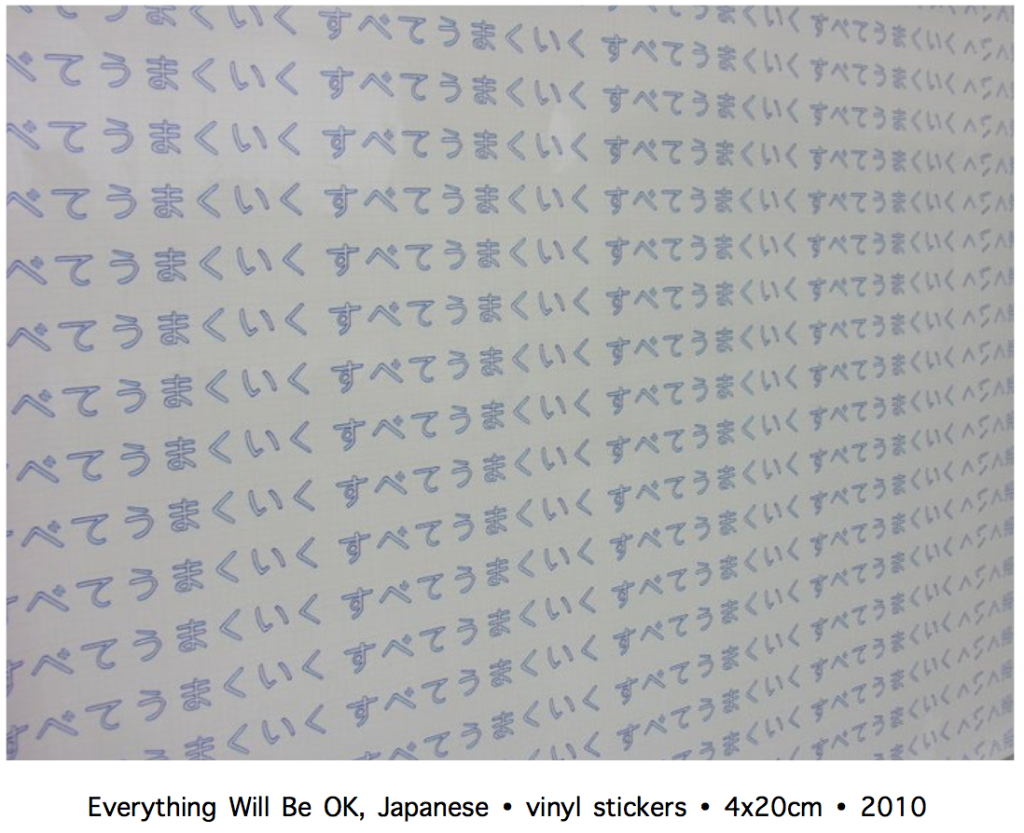

Eventually it lead me back to making images again, but with a new, perhaps more accurate, perception of the use of images. I believe the act of making is an art, but that making can be broad. So, to me, spray painting the words “Everything Will Be OK” on a train car, or titling a painting of an ex-girlfriend “Everything Will Be OK,” or drawing the space shuttle and titling it the same, all share the same impetus, and are extensions of the same pool of ideas or questions.

In Japan, for example, Everything Will Be OK was my project during a 2010 art residency there (ARCUS Projects). I placed the phrase throughout Tokyo, Moriya and Tskuba Cities. As in the USA, the phrase had an ironic and humorous context. When the Tōhoku earthquake struck in early 2011, the project entirely changed form. How was I to predict the affect of the ‘art’ on the context of the future, or on the viewer within the context of that event. That’s the beauty of art—when it’s allowed to grow past the frame or eradicate the canvas.

CC: Are you still working with any traditional media?

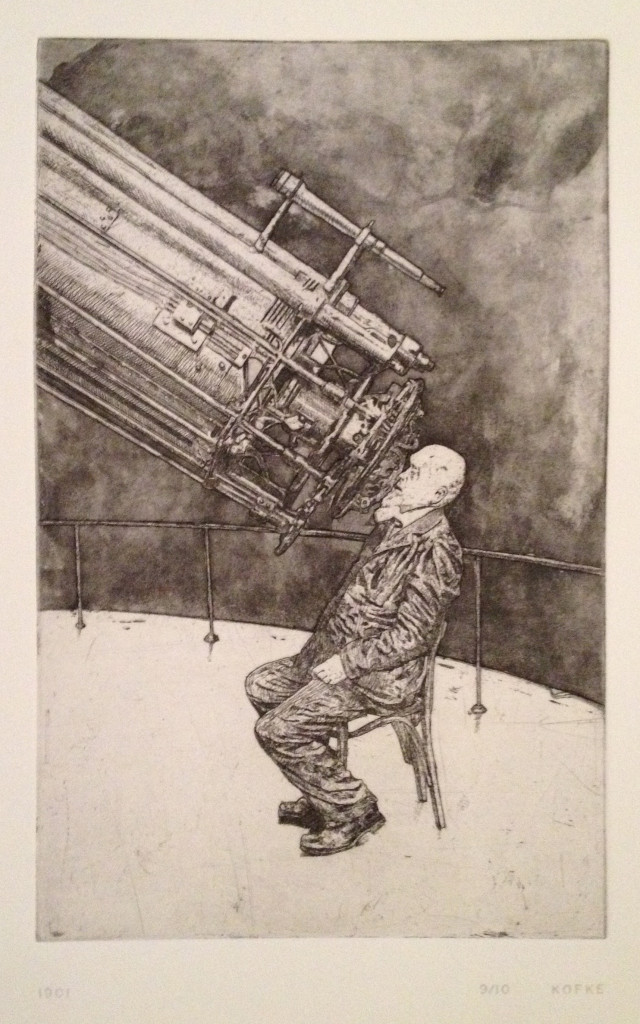

JK: Yes, I’ve come somewhat full circle: I’m again enamored by the directness and universal readability of the image. I’m also always learning new techniques and processes. I just wrapped up a show at Kai Lin Art titled Encyclopeadia. In this exhibition, I collaborated with Straw Hat Press to produce photogravures of drawings I made on vellum. The images I rendered were inspired by images found in image archives or an old encyclopedia set printed in the year of my birth. With this show, I tried to create a personal taxonomy of recent history using only images, and I used a printmaking process to attempt to replicate the aesthetic of 1970s and 1980s era encyclopedia illustrations. It continues to amaze me that we humans have produced concise compendiums of basically every important thing that has happened for new humans to read about, to catch us up to speed, in a sense.

CC: Some of your work contains Russian and Japanese characters. In addition to working on projects in both countries, has your work been influenced by traveling?

CC: Some of your work contains Russian and Japanese characters. In addition to working on projects in both countries, has your work been influenced by traveling?

JK: I remember leaving the U.S. for Russia for a week with $20 in my pocket. Somehow, day-by-day, things worked out in Russia, and I was magically fed each day and came back home with the same $20! You never know how resourceful you can be until you put yourself into a challenging situation.

Travel as an artist is important because the work produced overseas is genuine—because a sense of mystery for the viewer is almost guaranteed. In all my travels, the phrase “Everything Will Be ok” is an important continuous project. In Russia, Japan, Portugal or Tibet, the phrase in that native language is pure, and finding the artist is difficult due to the language barrier. It’s often a barrier the viewer cannot pass through, leaving him or her purely with the work. I don’t yet know if I travel to make art, or if I make art so as to travel—the two disciplines define me. I count myself lucky when I am able to combine these two passions.

CC: What else influences your work?

JK: Now we can come full circle and revisit the Challenger explosion of 1986. This is a lesson we as a culture are reminded of again and again: the Hindenburg was the biggest and the best; the Titanic was unsinkable; the global economy in 1917 would ensure no major war could ever happen. Over and over, we are reminded of our inherent condition of human fallibility—uncertainty might as well be an element. Technologies, especially modern ambitions, are not immune to the uncertain. On the subject of the uncertain, there is a book by a French mathematician named Rene Thom titled Catastrophe Theory published in 1979 that’s been very influential for me. His theory of mathematics used a type of algebraic geometry to attempt to understand and predict sudden change, as opposed to the gradual changes on which current science seems to concentrate. Within a few years, though, the theory and math were debunked because (and this is so beautiful) there is too much information and too many variables in reality for mathematics ever to be able to calculate the moment of catastrophe. Those with the Modernist mindset believed that with enough information, the future could be predicted.

Though debunked quantitatively, Thom’s ideas were successful qualitatively. His math helped develop perceptions of changes. And that perception change is what I find amazing. I try to produce the same effects in my work; catastrophe may be terrible, but there is beauty that can be derived from it if an alternate perception can be found. To learn from the failures of others. I wouldn’t say I fear or distrust modern technology. In fact, I’m a supporter of experimentation and the argument of progress. But I cannot ignore, and like to remind an audience that uncertainty, death, and loss is part of the price of continued life. Recently I’ve concluded that if my efforts as an artist could be summarized in one agenda, my agenda would be this: to confront, perhaps even attack, the decisions of the generations before ours. Some very difficult and dangerous forces have been introduced to humans in only the past 50 years. We are inheriting some very volatile situations and I think it remiss to discount historical decisions as just history.

CC: Talk a little about your upcoming and ongoing projects with WonderRoot and the Goat Farm.

JK: Currently, I’m wrapping up some experimental prints for WonderRoot’s CSA—some small etchings, solar plate and Xerox print tests. Those should be released to CSA participants next month. At the Goat Farm, I’m part of The Creatives Project’s studio artist residency and have a studio space there that has become my little wood shop. I’m also going to keep working with Straw Hat Press, as they are great printmakers. Both artists and collectors should look them up—not only are they making work with talented local artists (such as Nikita Gale and Curtis Bartone), they have a lot of works from artists that collectors should be interested in looking through. Beyond this, I’ll be relocating to the East Village of Manhattan soon. And I’m changing things up a bit in the coming months and producing a podcast reading of my grandfather’s diary kept during his war years, called War Diary WWII. It’s interesting to read his words and relive his history—knowing him as both a young man and an old man. Solo art shows will be at least a year away. I think it’s time to switch gears to various other projects to get away from the drafting table or etching press. But, whatever I’m working on, I’m hoping everything will be OK.

See more of Jason Kofke’s work here.